- Verily, a Google spinoff focused on medical tech, has raised billions in funding.

- Nearly six years in, Verily looks more like a scattershot collection of experiments than a game-changer.

- The company’s struggles are a case study in the power, and the limitations, of tech industry hubris.

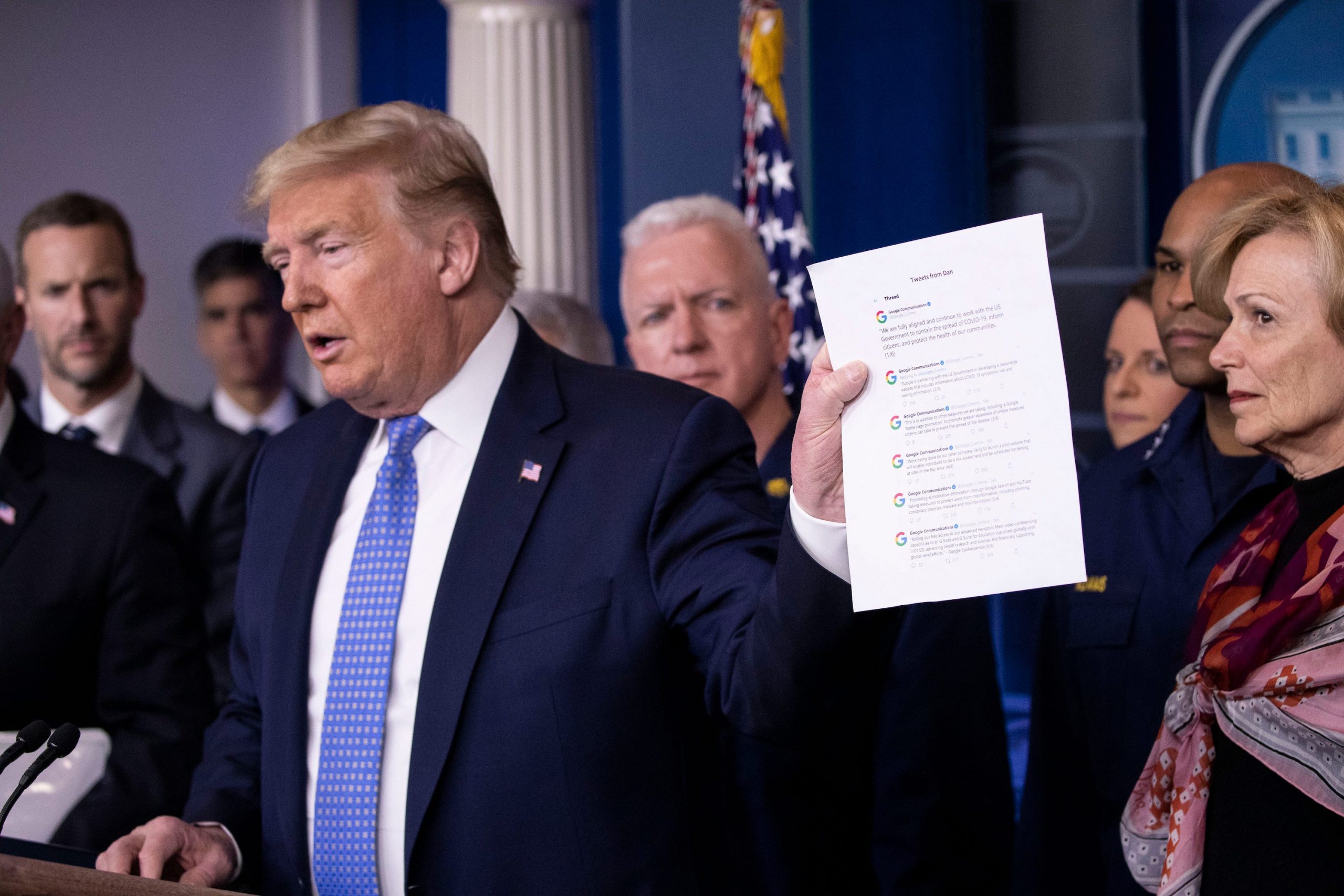

A year ago, as the United States confronted the first global pandemic in a century, Donald Trump assured a panicked nation that help was on the way. It was coming, he said, from Google, which planned to provide a digital platform to conduct Covid-19 testing. This came as a surprise to Google as well as to Verily Life Sciences, the Google-affiliated entity that had in fact told the White House it conceivably could pull off such a project.

That Trump didn’t know the difference between Google and Verily, or that no such initiative had yet begun, is more telling than merely as an early example of the misinformation and plain-old made-up stuff Trump would go on to spew from the Presidential lectern. A year later Verily isn’t much better known or understood, either to the general public or even the medical industry it purports to be revolutionizing. (It did, however, go on to build a well-received multi-state Covid testing operation.)

With this anniversary in mind, I have spent the last week or so trying to understand what exactly Verily is. What emerges is a picture of a secretive, exceedingly well-funded collection of medical-related science projects without a cohesive business to speak of.

That’s not to say the company has no commercial prospects. In fact, having raised a total of $2.5 billion from the likes of tech buyout firm Silver Lake, Singapore’s Temasek, and Google parent Alphabet itself, Verily has been able to invest in its five-plus years in existence in multiple potential opportunities, from a virtual diabetes clinic to cutting-edge medical devices to, most recently, a joint venture in a lucrative corner of the corporate insurance market. Less commercially, it also raises millions of genetically modified mosquitoes as part of an experiment to engineer away mosquito-borne diseases.

Yet in part because of its hush-hush ways and also the unresolved question of where it does and doesn't overlap with Google's own health initiatives, Verily remains nascent and confusing. In some ways it is more an investment firm focused on scattershot health-related bets than anything that looks like a traditional company.

Based just south of San Francisco in a facility that once belonged to the biotech firm Amgen, Verily declined to make any of its executives available for interviews. It did provide a few threadbare updates on its businesses, mostly information already on its web site. The company's CEO, Andy Conrad, rarely talks to the media. From a press relations standpoint, Verily seems to be traumatized by a 2016 article in the medical-industry publication Stat that detailed Conrad's early-career association with the real estate mogul David Murdock as well as conflicts between Verily and Google. Subsequent coverage has tended to focus on frequent management turnover and the company's fundraising, rather than what it does.

As it happens, Verily has roughly three ways of making money. (I'm told 2020 revenues were somewhere between $200 million and $300 million; it isn't anywhere close to profitability.) One is Project Baseline, a technology platform for organizing clinical research. Drug makers and other institutions pay to subscribe, and they also contract with Verily to run research projects. The second is Onduo, which focuses on diabetes treatment. The third is a dizzying array of joint projects with established pharmaceutical and medical device companies, each of which is designed to provide fees and equity upside for Verily. An example is Galvani Bioelectronics, a partnership with GSK that aims to cure diseases with implants that alter the body's neurological signals. (Luigi Galvani, an eighteenth- century Italian physician, is considered the father of bioelectromagnetics, says Wikipedia.)

The overlap with its founding cash cow, Google, remains unresolved. Alphabet and Google continue to approach health from multiple angles. Calico Life Sciences, another Alphabet company, has similar goals to Verily. Google Health is an aggregation of various health-related products and experiments. (Example: Care Studio, a search tool that organizes medical records for doctors.) And Google just bought FitBit, whose fitness tracker has health aspirations of its own.

The Google relationship cuts both ways. The company strenuously insists it operates at arms-length from Google, and it'd be a challenge to find Google branding, for example, on Verily's slick web site. Yet the company used a standard Google registration system to offer Covid tests, it signed a recent health provider deal in conjunction with Google Cloud, and as a full-fledged member of the Alphabet family its employees get access to Google's famous perks, like free food. Or at least they did when they used to come to the office. (This seems like a good place to disclose that I am married to a Google employee who does not work in a health-related part of the company.)

Conrad, the CEO, is universally acknowledged as Verily's driving force. One admirer describes him as a "chainsaw" and "not Googly," a cloying term Google people actually use (favorably) to describe a kind of cheerful team player. While Congrad's rough edges drive some away, he also is known as a master salesman, Verily's many commercial partnership being a testament to his skills. Says another fan: "He has an ability to get everybody in the room to cut off their arms."

Turnover at every level has been high. Andy Harrison, a top Verily dealmaker (and the brother of, Don Harrison, Google's top dealmaker), switched into a new Google position last fall and then this month joined Section 32, the venture firm run by ex-Google Ventures investor Bill Maris. Tom Stanis, Verily's longtime software chief, recently left to do a startup. One departing lower-level employee complained to me that the pandemic has sapped what was so alluring about working for a Google-related company: the free food, the exciting environment, the world-class facilities, and so on.

At the same time, $2.5 billion in funding makes it easy to recruit. The company hired a former Tesla chief financial officer, Deepak Ahuja, early last year. A few months ago it named Stephen Gillett, a veteran of Starbucks, Symantec, and other Alphabet postings, its chief operating officer. Weeks ago Verily hired veteran marketer Drew Panayiotou as chief marketing officer. This week he posted on LinkedIn that he's seeking "talented external communications team members with experience in public relations."

Verily certainly needs skilled storytellers because it is widely assumed to be planning an IPO well before its business matures. Iqvia, a leader in clinical trials technology, has a market valuation of $36 billion. Livongo, a startup with similar digital health aspirations as Onduo, sold itself to Teledoc last year for more than $18 billion. Verily, unformed as it is, has more of a commercial track record than several Silicon Valley concerns that have merged recently with blank-check vehicles known as SPACs.

Still, the company has much to prove. Medical businesspeople I spoke to think their industry would benefit from Verily's multidisciplinary approach. The nagging question is if its multiple-chips-on-the-roulette-table approach constitutes a colossal lack of focus or grand ambition that will yield one or two jackpots. Ultimately, Verily represents the epitome of the tech industry's hubris. Because its parent, Google, succeeded at one thing, a new form of advertising tied to an ingenious search algorithm, its offspring ought to be able to conquer any other field it desires.

The reality may end up being rather different.